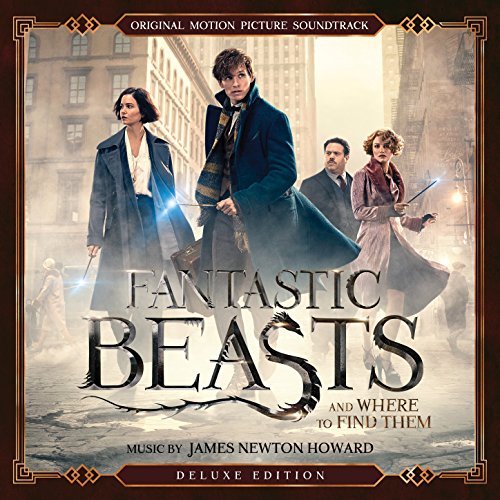

On its bright-red cover is a tattered sticker identifying the book as the “Property of: Harry Potter.” Even better, the inside of the book bears the marks of other young readers. Unlike a Wonderland stamp case or a T-shirt with Harry Potter’s image on it, items that the stories’ protagonists would never possess, the child’s copy of Fantastic Beasts becomes a border-crossing artifact. Instead, the text as object seems to have been magically transported from the shelves of Hogwarts to the hands of the child reader. Like Quidditch Through the Ages, published the same year, Fantastic Beasts does not continue the narrative of the series. Instead of bringing the reader into the world of the book, it brought a book from Hogwarts into the world of the reader. When it appeared in 2001, after the fourth book in the series, Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them offered “more” in a very different manner. Online, Harry Potter enthusiasts can visit the aptly named “Pottermore” site to be sorted into the proper House and to discover the form that their Patronus would take (mine is a dolphin). Wands choose children, butterbeer is consumed, and readers’ dreams come true. Universal Studios has gone to even greater lengths today, recreating whole sections of Hogwarts and entire rows of shops in Hogsmeade. Toad or spin through a mad tea party with Alice. In 1955, when Disney opened his first park, he created a space that can be thought of, in many ways, as a 3-D, pop-up anthology of children’s literature classics: The visitor in the 1950s could raft on the Mississippi with Tom and Huck, fly out the nursery window with Peter Pan, motor past police officers with Mr.

A stage version of Alice followed, as did an early silent film by Walt Disney several decades later. In the 19th century, fans of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland could purchase the “Wonderland Stamp Case,” endorsed by Lewis Carroll and sporting a transformable image of Alice holding the Duchess’ baby (or pig, once you pulled the tab). But the effort to provide more can take many other forms. The most obvious way to answer this desire is by the production of sequels. Readers, young and old, simply do not want the world of the book to end. The desire for more is a persistent force in the history of children’s literature. My students want what all readers of beloved books have wanted: more. From all of these accounts, one clear theme emerges. Some students mention a favorite character or a favorite magical object: wands, brooms, time-turners and chocolate frogs emerge from their nonmagical pens as they write out their literary memories. They remember gathering with family members for read-alouds and competing with classmates to see who could finish the new book first after a midnight release party. Students praise the series for capturing their imaginations, for teaching lessons about friendship and integrity, for inspiring them to love reading. Of course, they mention other books as well - The Giver, Little Women, Walk Two Moons - but only the Harry Potter series has had a book appear on every single list I’ve compiled. This happens not because I have been mistaken for the author (I can imagine far worse fates), but because I have asked the students in my children’s literature courses to write about a memorable book from their childhood. Advisory Board Member, Children's Studies MinorĮvery fall, tributes to J.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)